Water Quality Improvement

Treatment, Best Practices and Increased Water Storage

From the sawgrass marshes and tree islands of the Everglades to the mangrove stands along our coastlines and the wetlands, uplands, lakes and river floodplains of the interior, nutrients like phosphorus were once found at very low levels. With decades of residential and agricultural growth, the levels of nutrients and other trace pollutants making their way into these natural areas began to rise. As a result, native ecosystems as well as the plants and animals that are part of those systems began to change. To protect and restore these ecosystems, the South Florida Water Management District is working to remove excess nutrients and other pollutants, or prevent them from entering natural systems.

A number of efforts can effectively achieve this: building Stormwater Treatment Areas (constructed wetlands); requiring best management practices for agricultural and urban stormwater runoff; and creating surface or groundwater storage for seasonal water surpluses. All of these solutions for improving water quality are required elements of federal/state legislation for restoring the Greater Everglades (which includes the Kissimmee, Okeechobee and Everglades watersheds). They are also mandated by separate state legislation for water quality improvements in Lake Okeechobee and the Caloosahatchee and St. Lucie estuaries, as well as in the Everglades systems south of Okeechobee. Read more about these strategies to improve water quality in the sections below.

STATE AND FEDERAL LEGISLATION

- Everglades Forever Act & Settlement Agreement (F.S. 373.4592)

- Long-Term Plan for Achieving Water Quality Goals

- Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP)

- Northern Everglades and Estuaries Protection Act (F.S. 373.4595)

- Lake Okeechobee Protection Act

Improving Everglades Water Quality

Over the last 20 years, Florida has invested $1.8 billion in phosphorus control programs that have significantly improved Everglades water quality. Scientific monitoring shows at least 90 percent of the Everglades now meets ultra-clean water quality standards of 10 parts per billion or less for the nutrient.

Over the last 20 years, Florida has invested $1.8 billion in phosphorus control programs that have significantly improved Everglades water quality. Scientific monitoring shows at least 90 percent of the Everglades now meets ultra-clean water quality standards of 10 parts per billion or less for the nutrient.

The "Improving Everglades Water Quality" brochure has more details on how Florida has achieved this dramatic reduction in phosphorus levels and what it is doing to bring the entire Everglades ecosystem into compliance with stringent water quality standards.

Stormwater Treatment Areas (STAs)

Every plant needs nutrients to survive and thrive, but South Florida's native plants often are out-competed by other plants better able to use heavier nutrient loads. In constructed wetlands known as Stormwater Treatment Areas, some of these non-native plants with an appetite for high levels of nutrients are being used selectively to help remove excess nutrients, so that native plants can once again thrive.

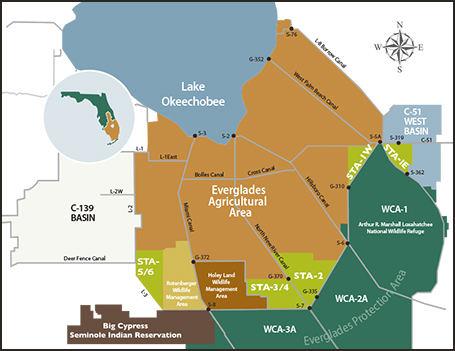

Stormwater Treatment Areas, or STAs, are constructed wetlands that remove and store nutrients through plant growth and the accumulation of dead plant material that is slowly converted to a layer of peat soil. Five STAs south of Lake Okeechobee are now removing excess nutrients from agricultural runoff water and, in some cases, runoff from urban tributaries, before discharging it into the Everglades and other natural areas. Two more STAs north of Lake Okeechobee are now in the planning stage.

STAs are comprised of parcels of land with compartments or cells with different plants predominating in each cell. Emergent plants, like cattails, pickerel weed and bulrush, remove nutrients and store them in peat-like soils as they decay. Submerged plants, including hydrilla, southern naiad and chara, also take phosphorus directly from the water in STAs.

Periphyton, which includes algae or bacteria found on or in the emergent and submerged vegetation, are another very important component of STAs that remove nutrients from the water. Typically, water is moved first through cells with emergent vegetation, then through cells with submergent vegetation. Water moves from one cell or compartment to the next, and at each stage gets cleaner.

Other methods involving chemical treatment were also tested, but proved to be far less effective in removing nutrients from the billions of gallons of water generated by the region's generous yearly rainfall. There are many treatment wetlands all over the country and the world, built at different scales for different purposes. The STAs built to improve the quality of water entering the Everglades system south of Lake Okeechobee are the largest of their kind in the world.

At present, these STAs south of Lake Okeechobee have an effective treatment area of 57,000 acres, which includes STA expansions completed in 2012 in the Everglades Agricultural Area (EAA) that added nearly 12,000 acres of treatment wetlands. North and east of Lake Okeechobee, STAs are also used to remove phosphorus from water flowing into the lake, St. Lucie Estuary and Indian River Lagoon.

As of April 2018, EAA Best Management Practices and Stormwater Treatment Areas together have removed more than 6,165 metric tons of total phosphorus from water entering the Everglades Protection Area. South Florida was impacted by two large storm events in Water Year 2018, and a record volume of 1.6 million acre-feet of water were treated in STAs, reducing phosphorus load by 77 percent. Two decades ago, before STAs were constructed, phosphorus concentrations in Everglades-bound waters averaged 170 parts per billion (ppb). Today, the concentrations in discharges to the Everglades have been as low as 11 ppb.

STA performance data are continually assessed and are reported monthly and yearly. An annual summary of STA performance is also available in the annual South Florida Environmental Report.

STAs – By the Numbers

STA-1 East, 5,000 acres, northeast of the Arthur R. Marshall Loxahatchee National Wildlife Refuge

STA-1 East, 5,000 acres, northeast of the Arthur R. Marshall Loxahatchee National Wildlife Refuge

- STA-1 West, 6,500 acres, northwest of the Arthur R. Marshall Loxahatchee National Wildlife Refuge

- STA-2, 15,500 acres (includes Compartment B expansion), west of Water Conservation Area 2

- STA-3/4, 16,300 acres in western Palm Beach County, the largest constructed wetland in the world

- STA-5/6, 13,700 acres (includes Compartment C expansion), in Hendry County, west of Rotenberger Wildlife Management Area

STA Operations

- Affected by weather (rainfall, drought, hurricanes), plant growth rates and invasion of undesirable plant species

- Water quality is continually monitored by scientists at District laboratories

- Operational decisions are made based on real-time data

- Scientists and technicians make approximately 27,000 visits per year to water quality monitoring stations

Agricultural Best Management Practices

Farming for winter vegetables, sugarcane, citrus, nursery plants or other crops is one of our region's largest industries. Agricultural practices can contribute excess nutrients or other pollutants to the rivers, lakes and wetlands of south and central Florida.

As part of the overall effort to decrease excess nutrients flowing into Florida's natural areas, most agricultural operations are now required to adopt Best Management Practices, or BMPs, to ensure that water flowing from agricultural lands is cleaner. BMPs include keeping livestock away from waterways and retaining and cleaning storm water or irrigation water "on-site." BMPs also include reducing the amount of water used for irrigation as well as minimizing fertilizers and pesticides or herbicides used on crops. To date, the combined use of STAs and agricultural BMPs has prevented more than 4,860 metric tons of phosphorus from entering the Everglades.

Urban Best Management Practices

Cities and communities also contribute nutrients and other pollutants to our region's rivers, lakes and wetlands. Storm water flowing over city streets or the rich green lawns and gardens that fill our urban and suburban landscapes can carry excess nutrients from the fertilizers and herbicides we use, as well as all the other contaminants that are a by-product of modern life.

Local governments and developers are also required to adopt Stormwater Best Management Practices, or BMPs, that make sure that water flowing into our natural ecosystems is cleaner. These BMPs include keeping direct urban stormwater runoff away from waterways, retaining and cleaning stormwater or irrigation water "on-site" and reducing the amount of water used for irrigation, as well as the type and quantity of fertilizers and pesticides or herbicides used on our landscapes.

Increased Water Storage

Before today's development, much of south and central Florida was land which stored water at least part of the year. Even while that storage has been reduced as the land has been converted for cities and farms, this development also makes it critical at times to quickly remove water from heavy storms or hurricanes to prevent catastrophic flooding.

To continue to be able to provide flood protection to people, while preventing excess flows to fragile ecosystems like the Everglades, Lake Okeechobee or coastal estuaries as the price of that flood control, increasing water storage is another key component of water quality protection and ecosystem restoration.

Above-ground impoundments or Water Preserve Areas as well as Aquifer Storage and Recovery pilot projects are now under way to provide additional water storage, so that excess flows are not "lost" to tide, and flows with excess nutrients or pollutants can be kept out of waterways and natural ecosystems. Some examples of plans to increase storage: A 10,500-acre reservoir is planned along the Caloosahatchee River (C-43 West). A reservoir and STA is also planned using approximately 55,000 acres as part of the Indian River Lagoon Project (C-44 Reservoir and STA). In Broward County, a Water Preserve Area (C-9 and C-11 Impoundment) of almost 7,000 acres is planned. In Miami-Dade County, the Biscayne Bay Coastal Wetlands Phase I project will help restore natural water flows to Biscayne Bay and Everglades National Park. And in Palm Beach County, the Fran Reich Preserve (Site 1 Impoundment, 1,600 acres) will collect runoff from the Hillsboro Watershed as well as from the Arthur R. Marshall Loxahatchee National Wildlife Refuge and Lake Okeechobee.